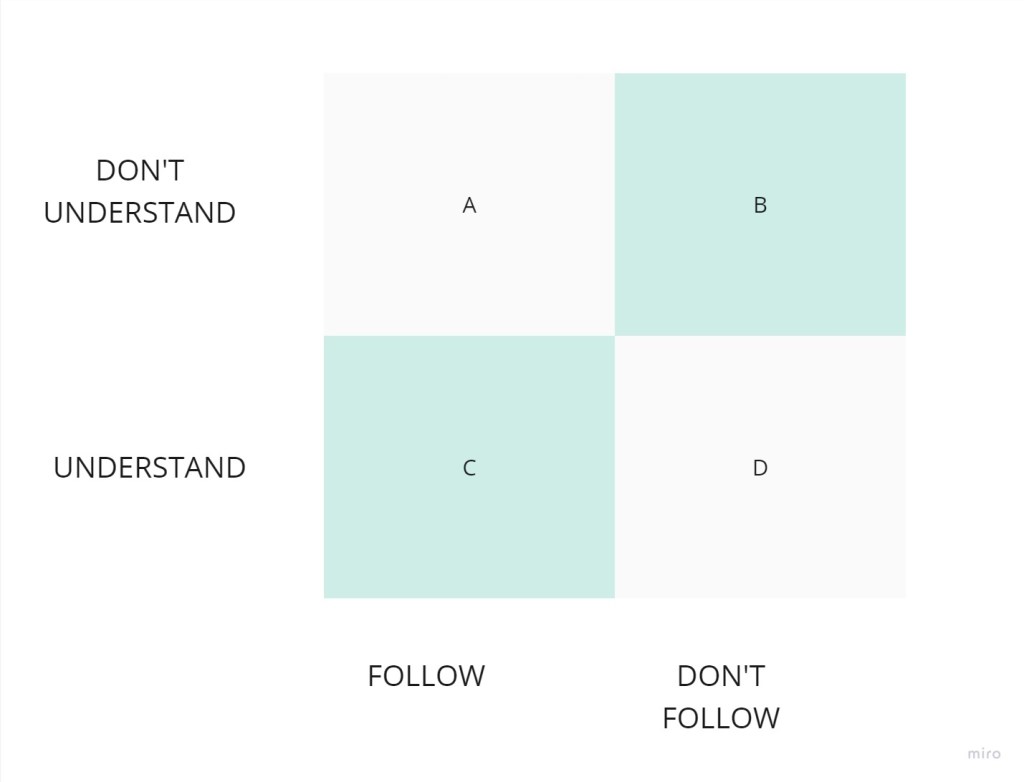

One of the most agonizing things for me when I fly on an airplane happens when flight attendants give the safety instructions. “Keep your seatbelts fastened and return your seat back to the upright position”, they say. I then observe how people react and mentally classify them into four different groups:

A – Those that have no idea why this is important but still follow the instructions. They either trust that the flight attendant has a legitimate reason for requiring this or simply don’t mind being obedient.

B – Those that don’t know why this is necessary and don’t follow the instructions. “Why bother doing it if it makes no sense to me?”

C – Those that understand the importance and therefore follow the guidelines. ‘Therefore’ is an important word here… They follow because they understand, not only because someone told them to. The action comes from their own self-interest.

D – Those that know why following those instructions is important but don’t follow it anyway. I don’t know why people act like this.

People in groups C and D are the most reasonable. They are acting accordingly to what they know.

My expectation that flight attendants will then explain why I should fasten my seatbelts and put my seat back in the upright position are never fulfilled. They constantly miss the opportunity to convert people from group B to group C and thus make their own job easier.

Instructions that seem arbitrary are everywhere. The thing is, they are certainly not arbitrary. Someone came up with them and had a reason for it. We might not agree with the reason, but there must be an explanation for why someone decided to create such rule. Knowing the explanation would both make us feel better when following them and enable us to disagree with substantiation.

Today, I came across an interesting research paper written by Sarah Gripshover and Ellen Markman, from Stanford University. They conducted some experiments to assert if children would eat more types of fruits/vegetables if they understood the importance of it. Understanding the importance of a rich diet is actually a complex cognitive function. You have to understand what are nutrients, that nutrients are found in food (although we can’t see them), that different food has different nutrients, that we need different nutrients for our body to function, etc. A child does not know all of that. Therefore, telling them that they need to eat broccoli **and carrot is, to their comprehension, totally arbitrary. The research findings show that indeed, if we give children a simplified model of nutrients and digestion, they will not only understand it but also act differently, eating more diversely by their own initiative.

Each person has their own mental model of understanding the world. We know that if we drop an object it will fall, because that is how we model the world. Our models constantly update according to what we learn and experience (learning might be merely this, altering our world models as our previous conceptions don’t match reality). We also make our decisions based on our models. I decide not to leave my glass of water close to the border of the table because I know that it could fall down and break. If my model of the world didn’t include gravity, I would act differently. In other words: what we know impacts what we do, even for little children.

I would love to conduct this experiment: take two airplanes, ready to take off. In one of them, give the usual instructions. In the other, don’t give any instructions at all, but explain people that the airplane might loose altitude suddenly and project every loose object to its ceiling; and that the position in which we find ourselves during a possible impact affects how it will be absorbed by our body. I’m not even sure that is really the reason, but its convincing to me. Then explain that we have a button to put our seat backs in different positions and that we have a seatbelt at our disposal.

Leave a comment