As you will see, at the end of this article, I propose a sort of “revolution” in how academic disciplines are organized. It is a strong word, so let’s make sure we attribute to it the same meaning.

Revolution derives from revolving, turning around, making circular movements. It was for a long time an astronomical terminology, describing the movement of planets around other celestial objects. The obvious realization where the word comes from actually surprised me, as since the 18th century this term has been used for something that seems opposite of the constant, predictable movement of planets… I wonder who chose this term to describe the French Revolution and why (my theoretical time machine would mostly be used to discover why some words were given for some things). Maybe he/she understood a new turn as a new chance, a new world. Another way to think of it, but I doubt it was the case, is that a revolution is always tied back to its origins. It is a defiance to a system, but originated in it, so totally influenced and dependent on it.

I’m using the term ‘revolution’ to describe a change in paradigm.

Most moments in history seem to be of incremental change. This is expected in any organizational system. Systems have self-protection mechanisms. You certainly noticed how difficult it is to act differently than what the system expects. It is like a force that drags you back to it, a systemic gravitational force. Nevertheless, sometimes in history there are moments of drastic change. A rupture in the system that usually comes from its decline.

My thought is that revolutions occur when there is a mismatch between the system’s development speed and its individuals development’s speed. It is simply the destabilization of the relationship between the micro components of a system (the individual) and the system’s macro behaviors that enable revolutions. If a system is changing either much slower or much faster than how its individuals change, they get organized and provoke a revolution. When a system does change in a more similar speed as to how their individuals think, there is not enough a gap for a revolution. The dissatisfaction doesn’t cross the threshold needed to start a revolution.

Let’s keep this for now.

I’m completely engrossed by Jürgen Renn’s book, The Evolution of Knowledge. I was searching for a theory that described the evolution of knowledge not at the individual level (how one person acquires and develops knowledge) but at a societal level and ChatGPT recommended me the book.

In the beginning of the book, the author presents one of the ideas that echoed the most in my head recently: the idea that the origin of new knowledge comes from ineffective communication between humans. That is oposite of what we might think, right? We should certainly think that good communication is they key to innovation. Well, to a certain extent.

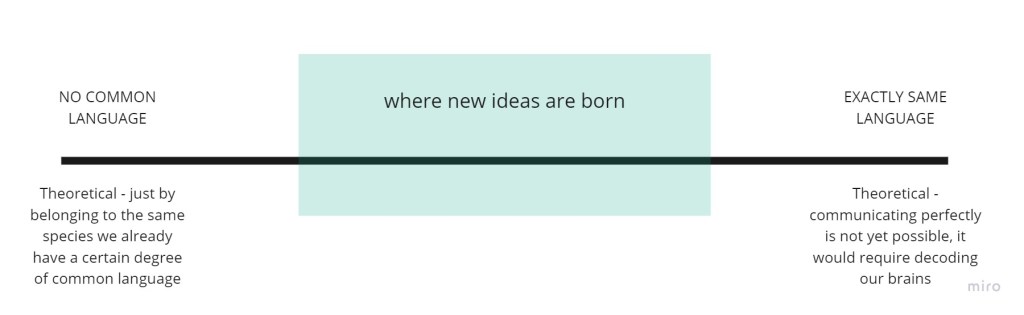

The point is, if everyone communicated extremely well, if it was possible for me to pass on my message to you perfectly, you would understand it just as I do. At the limit, perfect communication would lead to stagnation because people would think the same things. It is the fact that you understand what I say a bit different from what I meant that allows you to have different ideas than mine. The communication noise act as a sort of mutation of ideas, in the same way that genetic mutation is the source of variability in a species.

So, the goal is not to achieve perfect communication. This would be impossible anyway because our comprehension is affected by our experiences and no one has had exactly the same experiences – therefore no one’s brains has the same model. The only possibility of achieving perfect communication would be to decode each individual’s mental model and translate into the mental model of the other. I think it will be possible but not in the near future.

So, the goal is not to achieve perfect communication, but rather good enough communication, in a way that people still can engage with each other but with some variability. If they don’t speak at least a similar language, no exchange is possible, like people frustratingly trying to get around when speaking two completely different idioms. Going deeper into the analogy with the evolution of species, in a very rough manner: the perfect language would be like having only clones in a species, making it susceptible to changes in the environment; and the imperfect language would be like two different species that cannot breed.

How does it relate to the reorganization of the library?

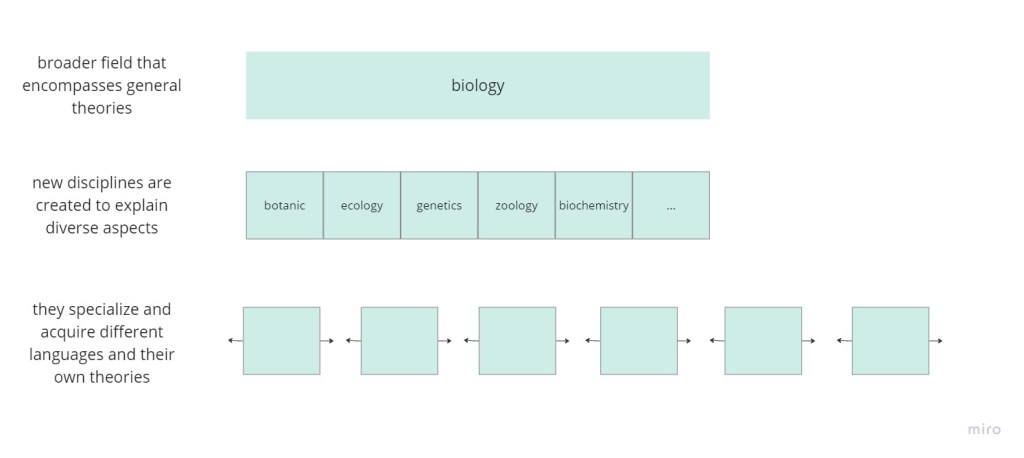

Academic disciplines, or fields of study, such as biology, geography, history, etc are categories of knowledge. We sometimes take this organization for granted, assuming it reflects some sort of natural division of the world. However, knowledge and it’s organization is purely a human construction. Disciplines have not always been organized the same way, specially because new fields were created when a group of recently discovered phenomenon could not fit the models of existing disciplines.

Organization is necessary for us to deal with the world. We simplify to cope with the complex. Sometimes, for very practical reasons, such as indexing books in a library or defining our roles in society (”I’m a biologist”). Humans need a common labeling system and so, disciplines are important. But the format we use to label knowledge influences knowledge itself, it is recursive. My argument is that this is what happens:

1 – Once a new discipline is created, members of that discipline get together intensively. They establish societies, working groups, magazines, forums and university departments specific for that field of study. As members of these group spend more together, they influence each other, and their language becomes more similar. They develop common terminology – jargons -, and generally accepted concepts. What Fleck calls a ‘thought collective’ is then formed. A sort of “sub-species” in evolution theory.

2 – At first, innovation and new discoveries flourish in this field of study. There have been many moments in history with booms of innovation in specific disciplines when they were recently created: mechanics, astronomy, biology, quantum physics, genetics, computer science…

3 – As time passes, innovation within that discipline declines because its innovation potential is exploited; because people within that field of study start thinking more similarly – a system is established, with its gravitation toward commonly accepted ideas -; and language becomes more homogeneous, resulting in fewer ‘mutations’… Innovation potential then shifts to the boundaries of the discipline: to interdisciplinary fields. Jürgen Renn also describes in his book the concept of ‘borderline problems’, phenomena not explained satisfactorily by the models of current fields of study, which relate to multiple domains of knowledge and that require a new combination of aspects from their often divergent models in order to be properly explained. In other words, that require a new discipline.

4 – The problem is… interdisciplinary work is difficult. Just as members of disciplines have acquired a common language among themselves, they have also distanced their language from that of members of other disciplines. They improved intra-communication at the expense of inter-communication. It’s fair to say from our daily lives experiences that people from one background have difficulties understanding people from other background: different academic departments with different terminology; the commercial team discussing with the technology team. I think what happens is something like this:

So…

If we want to innovate and discover new, unexpected solutions to problems that, within our current knowledge framework, appear to be ‘multi-disciplinary’, we may consider a revolution on how knowledge is structured – recreate the categories we have in our libraries. It would be so interesting to see what kinds of innovations would arise if we could scramble all current fields of study in a random way. Everybody seems to understand now that interdisciplinarity is important. So why do we remain so strongly attached to current disciplines?

Leave a comment